Terminology

European geologists have a terminology all their own when it comes to the Alps. Half of the trick to reading about the Alps is knowing what certain words mean. A few of the more common words are below.

flysch: [flish] a sedimentary sequence consisting of marine deposits of dark, thinly bedded, fine-grained marls, sandstones, shales, clays, and muds.

Flysch: an extensive, late Cretaceous to Oligocene sedimentary formation bordering the Swiss Alps and associated with the Alpine orogeny.

Insubric line: boundary between the European and Adriatic plates.

marl: a calcerous clay or mixture of clay and particles of calcite and dolomite, usually derived from shell fragments.

massif: a large block of rock or other structural feature within an orogenic belt that is usually older and more rigid than the surrounding rocks.

molasse: 1.a sedimentary sequence deposited during the Miocene period in southern Germany, subsequent to the rising of the Alps; composed primarily of soft, green sandstone associated with marl and conglomerates. 2.any similar sedimentary sequence.

nappe: a large, sheetlike rock unit that has been transported some distance forward over other rocks, either by thrust faulting, recumbent folding, or both. (what would be called a thrust sheet in the Western U.S.)

Definitions taken from Harcourt Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology

The Alps

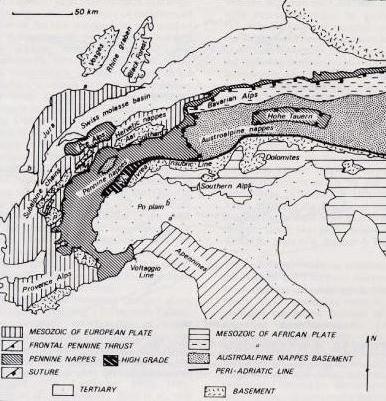

The Alpine chain of western Europe (Fig.1) resulted from the subduction of Tethyan oceanic crust followed by a continent-continent collision between Africa and Europe (Coward & Dietrich, 1989). The mountain belt contains slices of sediment and continental crust scraped off of both the European and African margins, as well as ophiolites. These "scrapings" or nappes are at most only a few kilometers thick each, but have produced pronounced crustal thickening as a whole. The Alpine orogeny was very complex and occurred in several phases from the middle Cretaceous to the Neogene, of which the collision between Europe and Africa was only one. Much of the earlier deformation has been overprinted in the Alps by the later mountain building in the Tertiary (Coward & Dietrich, 1989).

Figure 1

Structural zones within the western Alps (after Ramsay, 1963; Debelmas & Kerkhove, 1980; Trumpy, 1980).

from Coward & Dietrich, 1989

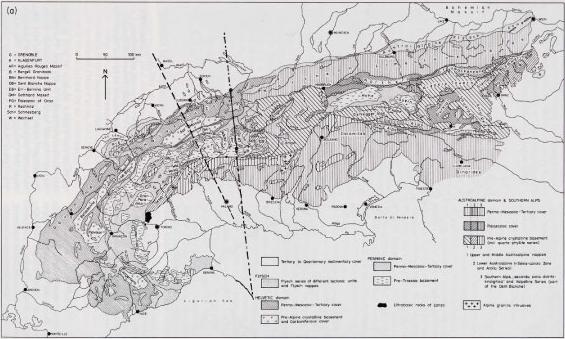

Figure 1a

Sketch map of the geologic-tectonic units in the Alps (after Frey et al., 1974).

from Mueller, 1989

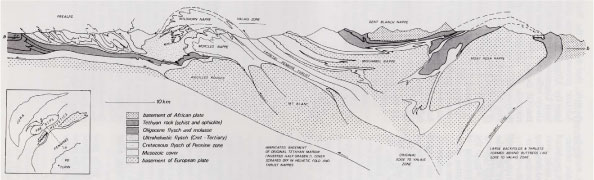

The main phase of the Alpine orogeny is defined as the continent-continent collision between the already-deformed margins of Europe and Africa. It comprises thrusting of Austro-Alpine units, i.e. nappes from the deformed southern margin as well as metamorphism and thrusting of the Pennine nappes (Coward & Dietrich, 1989). Next, the Brianconnais domain was deformed, followed by the formation of the major external structures, such as the Helvetic nappes in Switzerland. The time of the collision coincided with the complete subduction of the Tethyan ocean floor. The detachment horizon, from which the main nappes were stripped from the European lithosphere, rises from deep in the crust and from amphibolite facies rocks in the south to unmetamorphosed Jura mountains in the north. This upward progression of the detachment gives the Alps their asymmetric structure that verges north toward Europe (Coward & Dietrich, 1989). This is only a very first-order approximation of the Alpine orogeny. The plate kinematics are very complex as well as the complex deformation of already-deformed rocks (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Cross section through the Swiss Helvetic and Pennine Alps (section line shown on inset) after Escher et al., 1988. Left is NW and right is SE.

from Coward & Dietrich, 1989

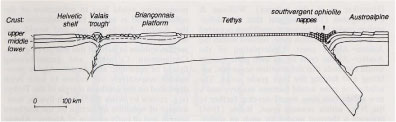

Figure 2a

The Cretaceous orogeny, according to Laubscher & Bernoulli (1982). The ophiolite nappes form a southvergent chain which is eventually thrust over the European plate during final closure of the Tethys.

from Coward & Dietrich, 1989

Swiss Molasse basin

The Swiss Molasse basin (Fig. 3) has long been recognized as the 'detritus washed down from the rising Alps' and deposited in a peripheral depression related to the Tertiary orogeny. Flexural bending of the down-going European plate under the thrust load advancing from the south is proposed as the principal foreland basin forming mechanism (Price, 1973; Dickinson, 1974; Turcotte & Schubert, 1982). This led to the characteristic downwarp flexure responsible for the wedge-shaped geometry of the basin in cross section and an upward flexure, the forebulge, located in the foreland. The present-day western Swiss Molasse basin is riding in a piggy-back fashion above a decollement horizon in Triassic evaporites (Deville et al., 1994). Thrust involvement has put an end to the subsidence history of the Molasse basin - no sediments younger than uppermost Serravallian have been found (Burkhard & Sommaruga, 1998). This indicates that the northwestern Alpine foredeep has been bypassed and cannibalized. Accordingly, the present-day Molasse basin is but a small remnant of a much larger foreland basin in a very advanced stage of its evolution (Burkhard & Sommaruga, 1998).

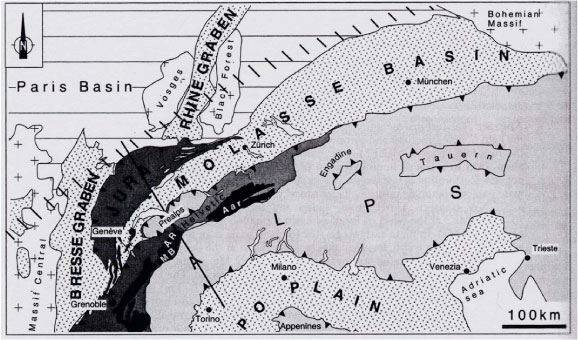

Figure 3

Location of the major Cenozoic basins: Rhine-Bresse Grabens, Molasse Basin and Po Plain with respect to the Alpine orogen. AR: Aiguilles Rouge massif; MB: Mont Blanc massif. The cross-hatched band in the foreland represents the assumed location of the present-day lithospheric forebulge.

from Burkhard & Sommaruga, 1998

[ Alpine Overview | Geology |

Geophysics | Geodynamics | Tectonic History |

References ]